Currently Empty: £0.00

Herb Histories: Ginger – The Mystery of A Universal Medicine

Ginger is a herb so characteristic of this time of year. Bringing warmth, fieriness and good health to our homes, it inspires within us what the autumnal colours in the leaves and the annual light installations do outside: that warm and cosy feeling. Helen brings us its story, one of mystery, and so for the fourth time, let Herb Histories with Helen begin…

Written by Helen Miller

The warm aroma and spicy taste of Ginger are familiar to most people around the world but Ginger doesn’t seem to be a wild plant.9 It’s currently thought to be a cultivar ‘developed’ in Southeast Asia or by the Indians and Chinese over 5,000 years ago. The exact origins of Ginger are unclear.1, 11 So, what other surprises does Ginger hold?

What’s In A Name?

The name Ginger was originally thought to come from the Sanskrit Singabera. In Mediaeval Latin this became Gingifra and then later Zingiber (hence the scientific/Latin name Zingiber officinale). The Anglo-Saxons then modified the Mediaeval Latin to Gingifre2, 8 and this became Ginger.9

There is some doubt about this though. The name Ginger could also have come from Tamil, one of the ancient languages of Southern India (still in use today), where the Ginger rhizome was called Ingiver. The rhizome was traded by the Arabians with Greeks and Romans and this was how Ginger made its way into Western Europe. The Tamil name for Ginger can be found in the Icelandic word for Ginger: Engifer; and in the Danish: Ingefaer; the Finnish: Inkivaari; and (slightly more loosely but more like ‘Ginger’) the Spanish: Jengibre.9

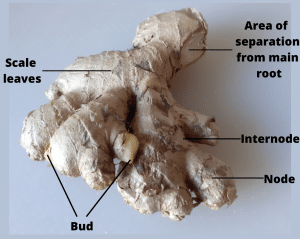

To summarise, no-one is really sure exactly where Ginger came from or how it got its name. The one thing we do know is that Ginger can only be propagated by splitting its rhizome, the flowers are usually sterile and rarely produce seed. This indicates that it has probably been cultivated by humans for many thousands of years.

So, now we’ve got that cleared up…

A Great Cure

What has been known about Ginger for a long time are its health benefits. In ancient India, it was not used as a spice in cooking, as was black pepper. It was used purely medicinally. It was called the Great Cure and used to treat a large number of common conditions, such as colds, joint pain and digestive issues, as well as given as an aphrodisiac. In Ayurvedic medicine it was used to treat gout, spots, and was important for reducing inflammation and as a carminative (aiding digestion). Since, Ginger is now known to contain a wide range of chemical constituents and this variety of uses is being shown to have some substance scientifically.9

In the second century AD, during the Roman times, Ginger was one of only a few items brought into the port at Alexandria on which duty was levied to safe-guard supplies for domestic use.9 The Romans, along with the Anglo-Saxons, seem to have thought that Ginger was the root of the Pepper-tree rather than a separate species.3, 8

Traditional Uses of Ginger

Another way Indians referred to Ginger was as the Universal Medicine. This was because it not only aided digestion but also helped blood circulation and the heart as well as warming the body.2 It was not only Indians who had a wide range of uses for Ginger; Chinese and Japanese systems of medicine both value it highly and this outlook was also shared by Arabs and Europeans. In his Herball (1633), Gerard says “Dioscorides reports that it is right good with meat in sauces, or otherwise in conditures; for it is of a heating and digesting quality, and is profitable for the stomach, and effectually opposes it self against all darkness of the sight; answering the qualities and effects of Pepper”.4 (‘…conditures;’ was a reference to seasonings.)

In A Modern Herbal, Mrs Grieves confirms the continued use of Ginger as a carminative and for colds. She also lists it as being useful for diarrhea when there is no inflammation, alcoholic gastritis and, externally, as a rubefacient (produces redness of the skin by dilating capillaries to increase blood flow to the area). She also discourages the use of Ginger essence due to the harm that can come from using it because of adulteration (adding things that aren’t Ginger Essence to increase profit).5 All of the uses she lists are basically what Ginger has been used for over hundreds of years. Namely aiding digestion and increasing blood circulation.

Modern Uses of Ginger

The potential uses of Ginger are many and include arthritis, rheumatism, indigestion, constipation, ulcers, atherosclerosis, hypertension, vomiting, asthma, diabetes mellitus and cancer. Ginger is also antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory.7 This wide range of medicinal uses is due to the wide range of chemical constituents found in Ginger. Over 60 active constituents have been identified and identified as either volatile or non-volatile. The volatile constituents give Ginger its aroma and flavor whereas the non-volatile constituents make-up the active components of the rhizome. These components include the gingerols, shogaols, paradols and zingerone.10

It is mainly the gingerols, shogoals and paradols that give Ginger its antioxidant property. This in turn makes it anti-inflammatory, meaning that Ginger can help reduce the occurrence of many diseases caused by inflammation, such as arthritis and atherosclerosis. The gingerol and shogoal constituents may also contribute to the neuroprotective effects of Ginger and help decrease memory loss due to ageing.10

An, as yet, unidentified constituent (or constituents) of Ginger has also been shown to reduce high blood-sugar and since it is not affected by heat it works whether the Ginger is consumed raw or cooked.6 All of this makes Ginger an excellent spice to add into cooking for the general maintenance of health. It also bears out the traditional uses of Ginger as an anti-inflammatory, digestive-aid that helps keep the circulatory and cardiovascular system healthy. A Universal Medicine indeed!

References

- Bode, A. M. and Dong, Z. (2011) The Amazing and Mighty Ginger, In Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects, Eds

- Bruton-Seal, J. and Seal, M. (2020) Kitchen Medicine:Household Remedies for Common Ailments, Merlin Unwin Books, Ludlow, Shropshire, UK.

- Everything You Didn’t Know About Ginger and Gingerbread (2014) Available at https://passionateomnivore.wordpress.com/2014/12/22/everything-you-didnt-know-about-ginger-and-gingerbread/ (Accessed: 09 November 2020).

- Gerard, J. (1633) The Herball: A General Historie of Plantes.

- Grieves, M. (1998) A Modern Herbal, Tiger Books International, London.

- Oludoyin, A. P. and Adegoke, S. R. (2014) Effect of ginger (Zingiber officinale) extracts on blood glucose in normal and streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. International Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2(2):32–35.

- Mashhadi, N. S., Ghiasvand, R., Askari, G., Hariri, M., Darvishi, L. and Mofid, M. R. (2013) Anti-oxidative and Anti-inflammatory Effects of Ginger in Health and Physical Activity: Review of Current Evidence, International Journal of Preventative Medicine, 4:S36-S42.

- Pollington, S. (2011) Leechbook: Early English charms, Plantlore and Healing, Anglo-Saxon Books.

- Prabhakaran Nair, K. P. (2013) The Agronomy and Economy of Turmeric and Ginger: The Invaluable Medicinal Spice Crops, Elsevier Inc., London.

- Shahrajabian, M. H., Sun, S. and Cheng, Q. (2019) Clinical aspects and health benefits of ginger (Zingiberofficinale) in both traditional Chinese medicine and modern industry, Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section B — Soil & Plant Science, DOI: 10.1080/09064710.2019.1606930

- World Health Organisation (1999) WHO Consultation on Selected Medicinal Plants (2nd) Ravello-Salerno, Italy.