Currently Empty: £0.00

Hildegard of Bingen: To Be Lost and Found

Gardening and all it entails can be understood as a physical connection to the past as so much of the activity has remained unchanged. The simple act of placing a seed in soil, giving it a sprinkling of water and excitedly waiting for nature, is wonderfully the same; we echo today actions made hundreds of years ago. We also carry with us the knowledge held by figures from different time periods, as their writings continue to share their learnings. It is no mean feat for a manuscript to survive hundreds of years, and those of Hildegard of Bingen, are cloaked in mystery and the changing status of lost to found to lost again. Read on for a brief introduction to this important figure.

Written by Kasia Howard

For many years now I have possessed a small copy of Hildegard’s Healing Plants, an extract and translation from Physica Hildegard of Bingen’s medieval work on health and healing. This book by the 12th century German abbess, has been a constant companion, usually placed, along with other essential books close to my workspace. But last August, as a flash flood ripped through the ground floor of the house, she was hastily grabbed and packed away into storage. I have since unpacked many stored boxes, but Hildegard remains elusive – a lost manuscript, an outcome which sits in keeping with many other masterpieces from the medieval period.

I have long been drawn to the earthy voices of garden writers, and especially those who understand gardening to be a holistic pastime that benefits mind, body and soul – and thank goodness, that there are more and more contemporary voices who are able to encourage us to think in this way. This is by no means a new phenomenon. The tradition of the Herbal is a long one. Defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as ‘a book containing the names and descriptions of herbs, or of plants in general, with their properties and virtues’, they go back millennia. Shénnóng Běn Cǎo Jīng Materia Medica is considered to be the oldest book on Chinese herbal medicine. Produced by the mythical Emporer Shennong, who lived around 2,800 BC, he founded Chinese herbal medicine.

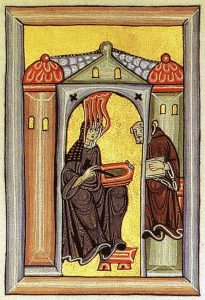

Sadly, the Oxford English Dictionary description of a Herbal sounds a bit pedestrian, but the authors of these early books were far from it. Hildegard of Bingen is regarded as a major 12th century mystic and prophet. She started having visions at the age of 6 and these spiritual and religious experiences led her to write not just two great books on medicine and healing, but a book of her visions called Scivias, as well as music and poetry. She even created an alternative alphabet, possibly used as secret code. Her two major medical works were Causae et Curae, a medical compendium, and Physica which has a strong affinity with Eastern medical traditions. Hildegard’s deep understanding of nature–trees, herbs, and animals—underpins a balanced spiritual and alchemical approach to healing.

Hildegard tended the large herb garden at Rupertsberg monastery, near the town of Bingen. Here medicines were prepared to treat members of the order as well as people from the surrounding countryside. At a time when most women could not read or write, she was widely accepted by physicians and religious healers of her time. No doubt she would have studied earlier manuscripts by Galen the physician of ancient Rome, and Pliny the Elder, but she also understood local folk lore and the magical qualities of plants; practising, observing and experimenting. She stressed the need for harmony between body, mind and spirit, very much like a naturopath or herbalist today.

Her works were lost for centuries and only in recent decades have scholars and scientists been able to study them, even going as far as statistically analysing the content to see if she had made it all up (the consensus was that she hadn’t). One wonders what might have been had her writing not been lost for so long. The contemporary reader finding her for the first time will be assured by the steady truth in her voice as she lists plants and describes their uses with an exemplary bedside manner.

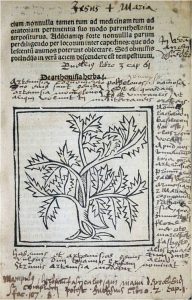

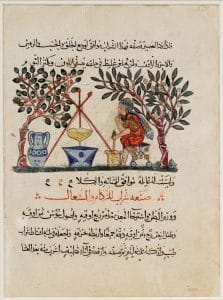

Other herbals which remained in circulation amongst religious communities and the wealthy, endured for centuries. One of the most famous in the western world is De Materia Medica by Dioscorides, written around 50-70 AD. It was translated into many languages and provided the foundation of many of the herbals that were written in later centuries. In the days before printing, copying manuscripts was commonplace. The original manuscript of the De Materia Medicahas never been found, so we do not know if it was ever illustrated, but an early version the Vienna Dioscorides (512 AD) has 435 illustrations of plants. Not all early herbals were illustrated, relying on descriptions of plants for identification purposes, but certainly as the use of printing techniques became more common place, illustrations became more frequent.

These early herbals are some of the most precious books that are held in our libraries and universities. Many have been lost over the centuries, and with them, so much important early knowledge. One of the quirkiest qualities of many early manuscripts are notes left in margins by owners, called ‘marginalia’ – which considering the rarity, even then, of these books seems to us outright vandalism (let alone the later habit of reusing pages, splitting manuscripts or cropping pages). From illustrations to notes, to random doodles, marginalia add an extra layer of information for us now about how the information was regarded and used, and can also tell us who owned the manuscript. All this extra information, however random it first seems, is invaluable to the historian and the herbalist alike.

The temporary loss of my copy of Hildegard is not a cause for major concern. Once I finish sifting through boxes it will no doubt surface. And when it does, I vow to use it more freely and add my own layer of notes and comments to its margins, in the spirit of the original herbal owners and users.

Kasia’s lost book is: Hildegard von Bingen’s Herbal: Healing Through Plants from the medieval classic Physica, Beacon Press Books. She is a spare time gardener and illustrator with an interest in medieval and early modern creative histories, you can follow her on instagram @kasia_howard.