Currently Empty: £0.00

Herb Histories: Daisies – The Day’s Eye in Love and War

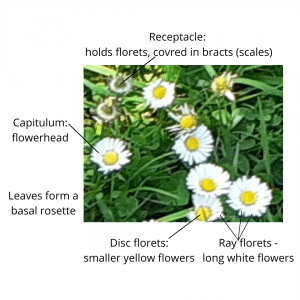

The humble daisy is rarely paid much attention until the late spring and summer, when the white and yellow blooms accent our lawns, roadsides and fields en masse. However, the common daisy is a hardy evergreen able to flower all year, belongs to a large family which includes the medicinal echinacea, and is suitable for pots (giving a wild, rustic feel if allowed to over spill old metal or terracotta pots). So often dismissed as a useless ‘weed’ we’re giving it some limelight as it kicks off the first Herb Histories of 2021. Without further ado, let Herb Histories with Helen begin…

Written by Helen Miller

A wound-healer during wars, a flower to keep small children safe and something sprinkled over the Earth by God to cheer parents up when their infant died. The superstitions and stories associated with Daisies are many and varied. But do any of them hold any truth?

What’s In A Name?

This is quite a straight forward one! Daisy comes from ‘day’s eye’. This is because the flower opens when the Sun comes up and closes at dusk (or in wet weather). Although it could also be a translation of the Latin ‘solis oculus’ meaning ‘sun’s eye’.9

Other common names for the Daisy are ‘Bruisewort’, ‘Bairnwort’ (from Scotland, refering to the joy of children gathering the flowerheads to make Daisy-chains) and ‘Llygad y Dydd’ (from the Welsh for ‘Eye of the Day’).5 Being a close relation to Arnica montana, Daisies are also sometimes called ‘Poor Man’s Arnica’.2

The Latin name for Daisy is Bellis perennis. The meaning of this is not quite as straight forward. The genus, Bellis, could be either from the Latin for war, ‘bellum’, or from the Latin for beauty, ‘bellus’. 5 Another idea is that it is after the nymph, Belides, who transformed into a Daisy to escape the attention of Vertumnus (the Roman God of Seasons and Gardens).5, 9

Puppies, Chains and Love

There are quite a few superstitions attached to the Daisy. Two, that I remember and am most familiar with are pulling the white petals off the flower as a form of love divination and the making of Daisy chains. When I was small, children would pick a flowerhead and pull off the white florets chanting ‘he loves me, he loves me not’.9 When they got to the end of the white florets, the last one left determined whether that person was loved or not by the person they were thinking about.

The second superstition of Daisy chains was so that Daisies could be worn by both sexes. By making the Daisies into a circle, evil spirits were prevented from passing though. This meant the children would not be stolen away by the Little/Faery Folk. Older children passed this skill onto the younger children, ensuring they all stayed safe.2

The last more unusual superstition associated with Daisies was that feeding a small puppy Daisy juice mixed with milk would prevent it from growing.4, 5 I have seen this recorded in a few places but have no idea where the idea came from. Culpepper does say that an infusion of Daisy mixed with asses milk is good for consumption of the lungs, but doesn’t mention puppies!3

Traditional Uses of Daisies

Gerard describes ‘the little Daisie’ (to separate it from the Ox-eye Daisy) as a cold, moist herb that could be used to alleviate all types of pain, but especially joint pain or that due to gout. The way he suggested using them was to combine them with butter and rub it on the afflicted area, “…but they work more effectually if Mallows be added thereto”.4

The main parts traditionally used were the leaves and the roots. The leaves were used as a ‘pot herb’ and could be added to salads, soups and stews1 to help ease stomach ache and inflammation of the intestines. So, Gerard seemed to think of it highly as a herb to be used in the digestive system. Culpepper and Mrs Grieves also recommend this use for an inflamed liver, with Mrs Grieves saying it should be taken as a distilled water.3, 5

Another recommendation from Gerard was to use them to ease fevers.4 In Mrs Grieves, she quotes a Dr Hill who, in 1777, used an infusion of Daisy leaves as a cure for a ‘Hectic fever’.

The other use for the leaves was as a wound healer for bruises and swellings.4 Mrs Grieves adds that it has ‘…a great reputation as a cure for fresh wounds…’ This was achieved using an ointment and applying it externally rather than taking the plant internally and this was apparently a well-known remedy in the fourteenth century.5 Culpepper says Daisies are ’…accounted good to dissolve congealed and coagulated blood…’.3

Gerard’s last recommendation for Daisies is sniffing the juice of the leaves and the roots to clear the head and shift mucus and clearing the eyes.4 Daisies are recorded in Old English records, as being hung about the house to drive out fleas.9

Modern Uses of Daisies

Recent research has found that the traditional wound healing use of Daisies has a strong scientific basis. One study found that dried Daisy flowers, powdered and extracted in n-butanol, accelerated wound-healing and decreased scarring on skin wounds.6

A later study found seven new saponins (constituents that have soap-like attributes and lower surface tension) in Daisy flowers. These saponins promote collagen synthesis, without any toxic side-effects. Collagen is the main structural constituent of skin. Therefore, the finding that Daisies contribute to collagen synthesis would explain why they have been used in wound healing. The actual mechanism of how this works, however, is still not known.8 One type of saponin in Daisy flowers has also been found to inhibit tumours.7

There are many superstitions about the cheerful little Daisy flowers that grow in our lawns, but their wound-healing properties are no longer in doubt.

Helen is a freelance copy and content writer, enthusiastic about science and history. To learn more about her work visit her Linked-In profile.

References

- Barker, J. (2001) The Medicinal Flora of Britain and Northwestern Europe, Winter Press

- Bruton-Seal, J. and Seal, M. (2017) Wayside Medicine: Forgotten plants and how to use them, Merlin Unwin Books, Ludlow, Shropshire, UK.

- Culpepper, N. (1653) Culpepper’s Complete Herbal: consisting of a comprehensive description of nearly all herbs with their medicinal properties and directions for compounding the medicines extracted from them, W. Foulsham & Co., Ltd., London.

- Gerard, J. (1633) The Herball: A General Historie of Plantes.

- Grieves, M. (1998) A Modern Herbal, Tiger Books International, London.

- Karakas, P. Karakas, A., Boran, I., Turker, A. U., Yalcin, F. N. and Bilensoy, E. (2012) The evaluation of topical administration of Bellis perennis fraction on circular excision wound healing in Wista albino rats, Pharmaceutical Biology, 50(8):1031-1037.

- Karakas, P. Sohretoglu, D., Liptaj, T., Stujber, M., Turker, A. U., Marak, J., Calis, I. and Yalcin, F. N. (2014) Isolation of an oleanane-type saponin active from Bellis perennis through antitumor bioassay-guided procedures, Pharmaceutical Biology, 52(8):951-955.

- Morikawa, T., Ninomiya, K., Takamori, Y., Nishida, E., Yasue, M., Hayakawa, T., Muraoka, O., Li, X., Nakamura, S., Yoshikawa, M. and Matsuda, H. (2015) Oleanane-type triterpene saponins with collagen synthesis-promoting activity from the flowers of Bellis perennis, Phytochemistry, 116: 203-212.

- Pollington, S. (2011) Leechbook: Early English charms, plantlore and healing, Anglo-Saxon Books